Alexander Selkirk (1676-1721) was a Scottish sailor whose experiences as a castaway on an island in the Pacific Ocean may very well have been one of the inspirations for Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. We cannot know for sure, because Defoe himself never made the connection explicit, and because Selkirk was not the only European sailor who had been so marooned and whose story could have come to Defoe’s attention. But Selkirk’s experience was the best known such adventure in England in the 1710s. Woodes Rogers, who was the captain of the ship that rescued Selkirk in 1709, had written up his story as part of his 1712 book A Cruising Voyage Round the World, which advertised the account of Selkirk’s rescue on its title page. Richard Steele interviewed Selkirk and published an account of their meeting in his journal The Englishman in 1713. Both of these accounts are printed below.

Selkirk spent more than four years alone on one of the Juan Fernandez islands, a small archipelago located about four hundred miles off the coast of modern-day Chile. He had been the navigator on the Cinque Ports, which was a privateer, essentially a pirate ship licensed by the British government to capture and harass Spanish and French ships during the War of the Spanish Succession (1703-1712). Selkirk had quarreled with Thomas Stradling, the captain of the Cinque Portes, arguing once the ship reached a small, uninhabited island, that they needed to make essential repairs before continuing. When Stradling refused, Selkirk in effect mutinied, demanding to be let off and seeking collaborators among the crew. This may well have been a bluff to force the captain’s hand. But Stradling obliged, letting Selkirk disembark with his gear, then refusing to let him back on when Selkirk changed his mind. Selkirk was right about the ship’s seaworthiness, however. The Cinque Portes was in no shape to continue, and sank just a few weeks after leaving Selkirk stranded; Stradling and the survivors of the crew spent months as as prisoners of the Spanish in Lima under very harsh conditions. Alone on his island, Selkirk struggled with months of depression but ultimately thrived. He found fresh water, ate native plums, berries, and crayfish, read the Bible, and hunted for goats, which he used for food and skinned for shelter and clothing. When he was rescued, he was in good health, but had trouble communicating with his rescuers, having not spoken to anyone in four years. Remarkably, Rogers returned Selkirk to service, and he continued as a member of Rogers’s crew for another two years.

Upon his return to England in 1711, Selkirk became a minor celebrity, and had a windfall of money as the reward he earned as his share of privateering booty both before and after his sojourn on the island. But Selkirk seems to have trouble adjusting to life on land, sometimes isolating himself in a cabin, drinking heavily. He married two women, at one point being married to both at the same time. In truth, he had always been a contentious person, fighting with his family and getting into trouble with the law. His fight with Stradling was not the first conflict he had had with an authority figure. The sea was Selkirk’s real home, and in 1720 he signed up for another privateering voyage. He died on that voyage in December 1721 off the coast of Africa, probably of yellow fever. He was 55 years old.

Recently, archeologists have returned to the island on which Selkirk was marooned, now known as Robinson Crusoe’s Island, and have identified his campsite. Most tantalizingly, they unearthed a piece of a navigational instrument that may have belonged to him.

Whether or not Alexander Selkirk is the inspiration for Defoe’s protagonist, his story is a remarkable one that many readers of Defoe’s book would surely have recalled.

Here are Rogers and Steele’s accounts.

from Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage round the World (1712)

Febr. 2. We stood on the back side along the South end of the Island, in order to lay in with the first Southerly Wind, which Capt. Dampier told us generally blows there all day long. In the Morning, being past the Island, we tack’d to lay it in close aboard the Land and about ten a clock open’d the South End of the Island, and ran close aboard the Land that begins to make the North-East side. The Flaws came heavy off shore, and we were force’d to reef our Top-fails when we open’d the middle Bay, where we expected to find our Enemy, but saw all clear, and no Ships in that nor the other Bay next the N W. These two Bays are all that Ships ride, in which recruit on this Island but the middle Bay is by much the best. We guess’d there had been Ships there, but that they were gone on sight of us. We sent our Yall ashore about Noon, with Capt. Dover, Mr. Frye, and six men, all arm’d; mean while we and the Dutchess kept turning to get in, and such heavy Flaws came off the Land, that we were forced to let fly our Topsail-Sheet, keeping all Hands to stand by our Sails, for fear of the Wind’s carrying ’em away: but when the Flaws were gone, we had little or no Wind. These Flaws proceeded from the Land, which is very high in the middle of the Island. Our Boat did not return, so we sent our Pinnace with the Men arm’d, to fee what was the occasion of the Yall’s stay; for we were afraid that the Spaniards had a Garrison there, and might ‘have seiz’d ’em. We put our a Signal for our Boat, and the Dutchess show’d a French Ensign. Immediately our Pinnace return’d return’d from the shore, and brought abundance of Craw-fish, with a Man cloth’d in Goat-Skins, who look’d wilder than the first Owners of them. He had been on the island four Years and four Months, being left there by Capt. Straddling in the Cinque-Ports; his Name was Alexander Selkirk a Scotch Man, who had been Master of the Cinque-Ports, a Ship that came here last with Capt. Dampier, who told me that this was the best Man in her; so I immediately agreed with him to be a Mate on board Our Ship. ‘Twas he that made the Fire last last night when he saw our Ships, which he judg’d to be English. During his stay here, he saw several ships pass by, but only two came in to anchor. As he went to view them, he found ’em to be Spaniards and retir’d from ’em; upon which they shot at him. Had they been French, he would submitted; but chose to risque his dying alone on the Island, rather than fall into the hands the Spaniards in these parts, because he apprehended they would murder him, or make a Slave of him in the Mines, for he fear’d they would spare no Stranger that might be capable of discovering the South-Sea. The Spaniards had landed, before he knew what they were, and they came so near him that he had much ado to escape; for they not only shot at him, but pursued him into the Woods, where he climb’d to the top of a Tree, at the foot of which they made water, and kill’d several Goats just by, but went off again without discovering him. He told us that he was born at Largo in the County of Fife in Scotland, and was bred a sailor from his Youth. The reason of his being left here was a difference betwixt him and his Captain which, together with the Ships being leaky, made him willing rather to stay here, than go along with him at first and when he was at willing, the Captain would not receive him. He had been in the Island before to wood and water, when two of the Ships Company were left upon it for six Months till the Ship return’d, being chas’d thence by two French South Sea Ships.

He had with him his Clothes and Bedding; with a Firelock, some Powder, Bullets, and Tobacco, a Hatchet, a Knife, a Kettle, a Bible, some practical Pieces, and his Mathematical Instruments and Books. He diverted and provided for himself as well as he could; but for the first eight months had much ado to bear up against Melancholy; and the Terror of being left alone in such a desolate place. He built two Hutts with Piemento Trees; covered them with long Grass, and lin’d them with the Skins of Goats, which he kill’d with his Gun as he wanted, so long as his Powder lasted; which was but a pound; and that being near spent, he got fire by rubbing two sticks of Piemento Wood together upon his knee. In the lesser Hutt, at some distance from the other, he dress’d his Victuals, and in the larger he slept, and employ’d himself in reading, singing Psalms, and praying; so that he said he was a better Christian while in this Solitude than ever he was before, or than, he was afraid, he should ever be again. At first he never eat any thing till Hunger constrained him; partly for grief, and partly for want of Bread and Salt; nor did he go to bed till he could watch no longer: the Piemento Wood, which burnt very clear, serv’d him both for Firing and Candle; and refreshed him with its fragrant Smell.

He might have had Fish enough, but could not eat ’em for want of Salt, because they occasioned Looseness; except Crawfish, which are there as large as our Lobster, and very good: These he sometimes boil’d, and at other times broil’d; as he did his Goats Flesh, of which he made very good Broth, for they are not so rank as ours: he kept an Account of 500 that he kill’d while there, and caught as many more, which he mark’d on the Ear and let go. When his Powder fail’d, he took them by speed of foot; for his way of living and continual Exercise of walking and running, cleared him of all gross Humours, so that he ran with wonderful Swiftness thro’ the Woods and up the Rocks and Hills, as we perceiv’d when we employ’d him to catch Goats for us. We had a Bull-Dog, Which we sent with several of our nimblest Runners, to help him in catching Goats; but he distanc’d and tir’d both the Dog and the Men, catch’d the Goats, and brought ’em to us on his back. He told us that his Agility in pursuing a Goat had once like to have cost him his Life; he pursu’d it with so much Eagerness that he catch’d hold of it on the brink of a Precipice, of which he was not aware, the Bushes having hid it from him; so that he fell with the Goat down the said Precipice a great height, and was so stun’d and bruised with the fall that he narrowly escaped with his Life, and when he came to his Senses found the Goat dead under him. He lay there about 24 hours, and was scarce able to crawl to his Hutt, which was about a mile distant, or to stir abroad again in ten days.

He cam at last to relish his Meat well enough without Salt or Bread, and in the Season had plenty of good Turnips, which had been sow’d there by Capt. Dampier’s Men, and have now overspread some acres of Ground. He had enough of good Cabbage from the Cabbage-Trees, and season’d his Meat with the Fruit of the Piemento Trees, which is the fame as the Jamaica Pepper, and smells deliciously. He found there also a black Pepper call’d Malagita, which was very good to expel Wind, against Griping of the Guts.

He soon wore out all his Shoes and Clothes by running thro’ the Woods; and at last being forced to shift without them, his Feet became so hard that he ran every where without Annoyance: and it was some time before he could wear Shoes after we found him; for not being us’d to any so long, his Feet swell’d when he came first to wear ‘em again.

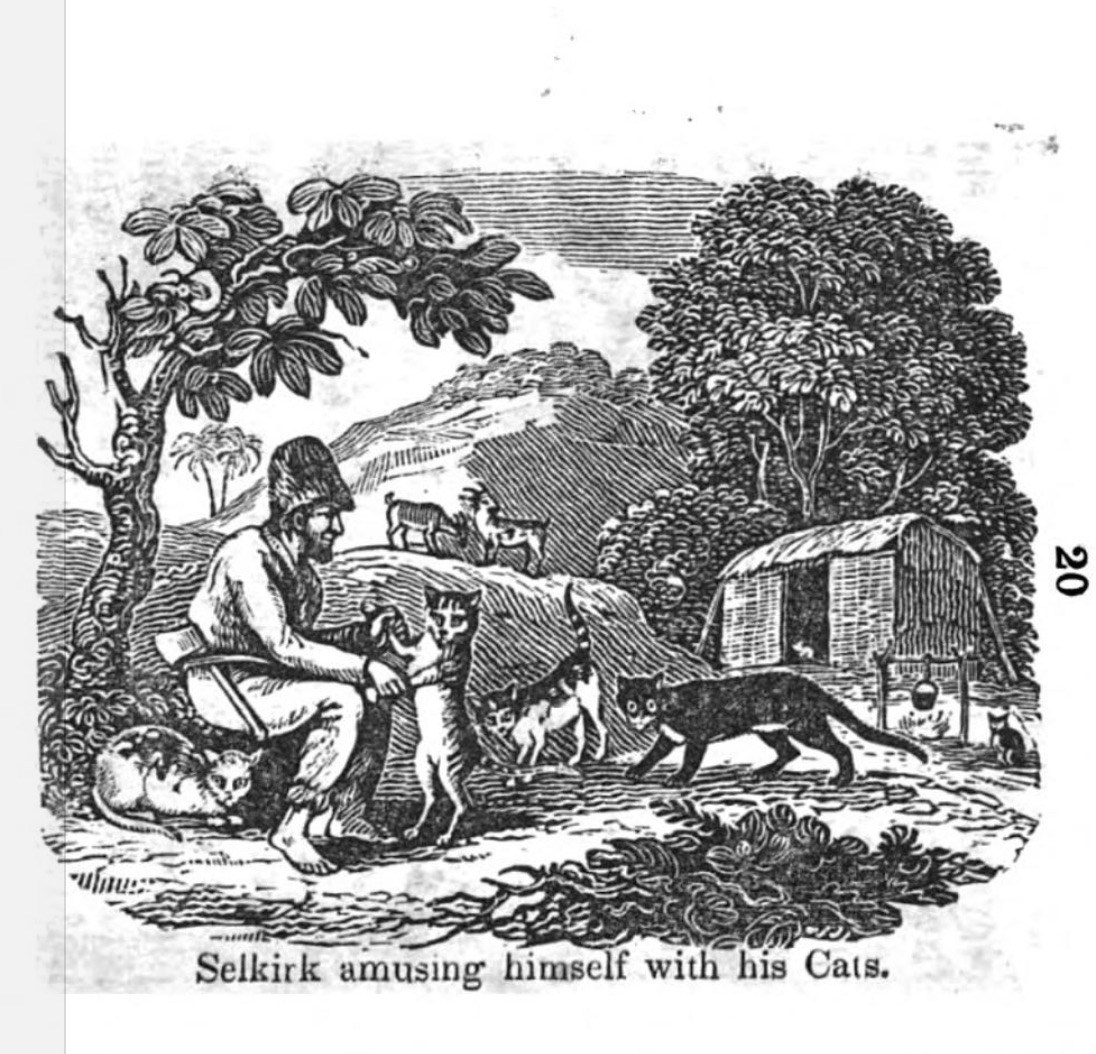

After he had conquered his Melancholy, he diverted himself sometimes by cutting his Name on the Trees and the Time of his being left and Continuance there. He was at first much pester’d with Cats and Rats, that had bred in great numbers from some of each species which had got ashore from Ships that put in there to wood and water. The stats gnaw’d his Feet and Clothes while asleep,: which oblig’d him to cherish the Cats with his Goats-flesh; by which many of them became so tame that they would lie about him in hundreds, and soon delivered him from the Rats. He likewise tam’d some Kids, and to divert himself would now and then sing and dance with them and his Cats; so that by the Care of Providence and Vigour of his Youth, being now but about 30 years old, he came at last to conquer all the Inconveniences of his Solitude, and to be very easy. When his Clothes wore out, he made himself a Coat and Cap of Goat-Skins, which he stitch’d together with little Thongs of the fame, that he cut with his Knife. He had no other Needle but a Nail; and when his Knife was wore to the back, he made others as well as he could of some Iron Hoops that were left ashore, which he beat thin and ground upon Stones. Having some Linen Cloth by him, he sow’d himself Shirts with a Nail and stitch’d ’em with the Worsted of his old Stockings, which he pull’d out on purpose. He had his last Shirt on when we found him on the Island.

At his first coming on board us, he had so much forgot his Language for want of Use, that we could scarce understand him, for he seem’d to speak his words by halves. We offered him a Dram, but he would not touch it, having drank nothing but Water since his being there, and ’twas some time before he could relish our Victuals.

He could give us an account of no other Product of the Island than what we have mentioned, except small black Plums, which are very good, but hard to come at, the Trees which bear ’em growing son high Mountains and Rocks. Piemento Trees are plenty here, and we saw some of 60 foot high, and about two yards thick and Cotton Trees higher, and near four fathom round in the Stock.

The Climate is so good, that the Trees and Grass are verdant all the Year. The Winter lasts no longer than June and July, and is not then severe, there being only a small Frost and a little Hail, but sometimes great Rains. The Heat of the Summer is equally moderate, and there’s not much Thunder or tempestuous Weather of any sort. He saw no venomous or savage Creature on the Island, nor any other sort of Beast but Goats, &c. as above mentioned; the first of which had been put ashore here on purpose for a Breed by Juan Fernando, a Spaniard, who settled there with some Families for a time, till the Continent of Chili began to submit to the Spaniards, which being more profitable, tempted them to quit this Island, which is capable of maintaining a good number of people, and of being made so strong that they could not be easily dislodged.

Ringrose in his Account of Capt. Sharp’s Voyage and other Buccaneers, mentions one who had escaped ashore here out of a Ship which was cast away with all the rest of the Company, and says he liv’d five years alone before he had the opportunity of another Ship to carry him off. Capt. Dampier talks of a Moskito Indian that belonged to Capt. Watlin, who being a hunting in the Woods when the Captain left the Island, liv’d here three years alone, and shifted much in the fame manner as Mr. Selkirk did, till Capt. Dampier came hither in 1684, and carry’d him off. The first that went ashore was one of his Countrymen, and they saluted one another first by prostrating themselves by turns on the ground, and then embracing. But whatever there is these Stories, this of Mr. Selkirk I know to be true; and his Behaviour afterwards gives me reason to believe the Account he gave me how he spent his time, and bore up under such an Affliction, in which nothing but the Divine Providence could have supported any Man. By this one may fee that Solitude and Retirement from the World is not such an unsufferable State of Life as most Men imagine, especially when People are fairly call’d or thrown into it unavoidably, as this Man was, who in all probability must otherwise have perished in the Seas, the Ship which left him being cast away not long after, and few of the Company escap’d. We may perceive by this Story the Truth of the Maxim, That Necessity is the Mother of Invention, since he found means to supply his Wants in a very natural manner, so as to maintain his Life, tho not so conveniently, yet as effectually as we are able to do with the help of all our Arts and Society. It may likewise instruct us, how much a plain and temperate way of living conduces to the Health of the Body and the Vigour of the Mind, both which we are apt to destroy by Excess and Plenty, especially of strong Liquor, and the Variety as well as the Nature of our Meat and Drink: for this Man, when he came to our ordinary Method of Diet and Life, tho he was sober enough, lost much of his Strength and Agility. But I must quit these Reflections, which are more proper for a Philosopher and Divine than a Mariner, and return to my own Subject.

from Richard Steele, The Englishman (1713)

Under the Title of this Paper, I do not think it foreign to my Design, to speak of a Man born in Her majesty’s Dominions, and relate an Adventure in his Life so uncommon, that it’s doubtful whether the like has happen’d to any other of human Race. The Person I speak of is Alexander Selkirk, whose Name is familiar to Men of Curiosity, from the Fame of his having lived four years and four Months alone in the Island of Juan Fernandez. I had the pleasure frequently to converse with the Man soon after his Arrival in England, in the Year 1711. It was matter of great Curiosity to hear him, as he is a Man of good Sense, give an Account of the different Revolutions in his own Mind in that long Solitude. When we consider how painful Absence from Company for the space of but one Evening, is to the generality of Mankind, we may have a sense how painful this necessary and constant Solitude was to a Man bred a Sailor, and ever accustomed to enjoy and sufFer, eat, drink, and sleep, and perform all Offices of Life, in Fellowship and Company. He was put ashore from a leaky Vessel, with the Captain of which he had had an irreconcileable difference; and he chose rather to take his Fate in this place, than in a crazy Vessel, under a disagreeable Commander. His Portion were a Sea-Chest, his wearing Cloaths and Bedding, a Fire-lock, a Pound of Gun-powder, a large quantity of Bullets, a Flint and Steel, a few Pounds of Tobacco, an Hatchet, a Knife, a Kettle, a Bible, and other Books of Devotion, together with Pieces that concerned Navigation, and his Mathematical Instruments. Resentment against his Officer, who had ill used him, made him look forward on this Change of Life, as the more eligible one, till the Instant in which he saw the Vessel put off; at which moment, his Heart yearned within him, and melted at the parting with his Comrades and all Human Society at once. He had in Provisions for the Sustenance of Life but the quantity of two Meals, the Island abounding only with wild Goats, Cats and Rats. He judged it most probable that he should find more immediate and easy Relief, by finding Shell-fish on the Shore, than seeking Game with his Gun. He accordingly found great quantities of Turtles, whose Flesh is extreamly delicious, and of which he frequently eat very plentifully on his first Arrival, till it grew disagreeable to his Stomach, except in Jellies. The Necessities of Hunger and Thirst, were his greatest Diversions from the Reflection on his lonely Condition. When those Appetites were satisfied, the Desire of Society was as strong a Call upon him, and he appeared to himself least necessitious when he wanted every thing; for the Supports of his Body were easily attained, but the eager Longings for seeing again the Face of Man during the Interval of craving bodily Appetites, were hardly supportable. He grew dejected, languid, and melancholy, scarce able to refrain from doing himself Violence, till by Degrees, by the Force of Reason, and frequent reading of the Scriptures, and turning his Thoughts upon the Study of Navigation, after the Space of eighteen Months, he grew thoroughly reconciled to his Condition. When he had made this Conquest, the Vigour of his Health, Disengagement from the World, a constant, chearful, serene Sky, and a temperate Air, made his Life one continual Feast, and his Being much more joyful than it had before been irksome. He now taking Delight in every thing, made the Hutt in which he lay, by Ornaments which he cut down from a spacious Wood, on the side of which it was situated, the most delicious Bower, fann’d with continual Breezes, and gentle Aspirations of Wind, that made his Repose after the Chase equal to the most sensual Pleasures.

I forgot to observe, that during the Time of his Dissatisfaction, Monsters of the Deep, which frequently lay on the Shore, added to the Terrors of his Solitude; the dreadful Howlings and Voices seemed too terrible to be made for human Ears; but upon the Recovery of his Temper, he could with Pleasure not only hear their Voices, but approach the Monsters themselves with great Intrepidity. He speaks of Sea-Lions, whose Jaws and Tails were capable of seizing or breaking the Limbs of a Man, if he approached them: But at that Time his Spirits and Life were so high, and he could act so regularly and unconcerned, that meerly from being unruffled in himself, he killed them with the greatest Ease imaginable: For observing, that though their Jaws and Tails were so terrible, yet the Animals being mighty slow in working themselves round, he had nothing to do but place himself exactly opposite their Middle, and as close to them as possible, and he dispatched them with his Hatchet at Will.

The Precaution which he took against Want, in case of Sickness, was to lame Kids when very young, so as that they might recover their Health, but never be capable of Speed. These he had in great Numbers about his Hutt; and when he was himself in full Vigour, he could take at full Speed the swiftest Goat running up a Promontory, and never failed of catching them but on a Descent.

His Habitation was extremely pester’d with Rats, which gnaw’d his Cloaths and Feet when sleeping. To defend him against them, he fed and tamed Numbers of young Kitlings, who lay about his Bed, and preserved him from the Enemy. When his Cloaths were quite worn out, he dried and tacked together the skins of Goats, with which he cloathed himself, and was enured to pass through Woods, Bushes, and Brambles with as much Carelessness and Precipitance as any other Animal. It happened once to him, that running on the Summit of a Hill, he made a Stretch to seize a Goat, with which under him, he fell down a Precipice, and lay sensless for the Space of three Days, the Length of which Time he Measured by the Moon’s Growth since his last Observation. This manner of life grew so exquisitely pleasant, that he never had a Moment heavy upon his Hands; his Nights were untroubled, and his Days joyous, from the Practice of Temperance and Exercise. It was his Manner to use stated Hours and Places for Exercises of Devotion, which he performed aloud, in order to keep up the Faculties of Speech, and to utter himself with greater Energy.

When I first saw him, I thought, if I had not been let into his Character and Story, I could have discerned that he had been much separated from Company, from his Aspect and Gesture; there was a strong but chearful Seriousness in his Look, and a certain Disregard to the ordinary things about him, as if he had been sunk in Thought. When the Ship which brought him off the Island came in, he received them with the greatest Indifference, with relation to the Prospect of going off with them, but with great Satisfaction in an Opportunity to refresh and help them. The Man frequently bewailed his Return to the World, which could not, he said, with all its Enjoyments, restore him to the Tranquility of his Solitude. Though I had frequently conversed with him, after a few Months Absence he met me in the Street, and though he spoke to me, I could not recollect that I had seen him; familiar Converse in this Town had taken off the Loneliness of his Aspect, and quite altered the Air of his Face.

This plain Man’s Story is a memorable Example, that he is happiest who confines his Wants to natural Necessities; and he that goes further in his Desires, increases his Wants in Proportion to his Acquisitions; or to use his own Expression, I am now worth 800 Pounds, but shall never be so happy, as when I was not worth a Farthing.