Phillis Wheatley (c 1753-1781) was the first African-American woman to publish a volume of her own poetry. She was born in west Africa and was brought by ship to Boston in July, 1761; she was believed to be seven or eight years old. The slave ship that carried her was called the Phillis, and she was given that name upon her arrival; there is no record of her African name and we do not know anything about how she was captured and enslaved. She was purchased by the Wheatleys, a well-off and prominent Boston family. John Wheatley was originally a tailor who branched out into a substantial business in wholesaling, shipping, and money-lending; his wife Susanna became an active supporter of Methodist and Presbyterian missionaries who came from England to preach in the colonies. When they purchased Phillis, the Wheatleys had eighteen-year-old twins, Nathaniel and Mary, and several other slaves working in their household.

The Wheatleys seem quickly to have recognized Phillis’s precocious talents with language, and taught her to read English, almost certainly starting with the Bible. Before long, however, she was reading the works of English poets like Alexander Pope and John Milton, as well as English translations of classical poets like Homer, Virgil, and Ovid. John Wheatley testified that within sixteen months of her arrival, she was able to read even the most difficult parts of the Bible, which is extraordinary for any nine-year-old and pretty much unprecedented for African-American slaves in the eighteenth century, most of whom were never taught to read by their masters; white slave owners generally feared teaching their slaves how to read and write lest they use those tools to work against the system that enslaved them, and in many places it was illegal to teach slaves to read. Phillis began publishing poems in New England newspapers at the age of fourteen, and continued to publish occasional poetry (that is, poems on particular current occasions or events) in newspapers over the next several years.

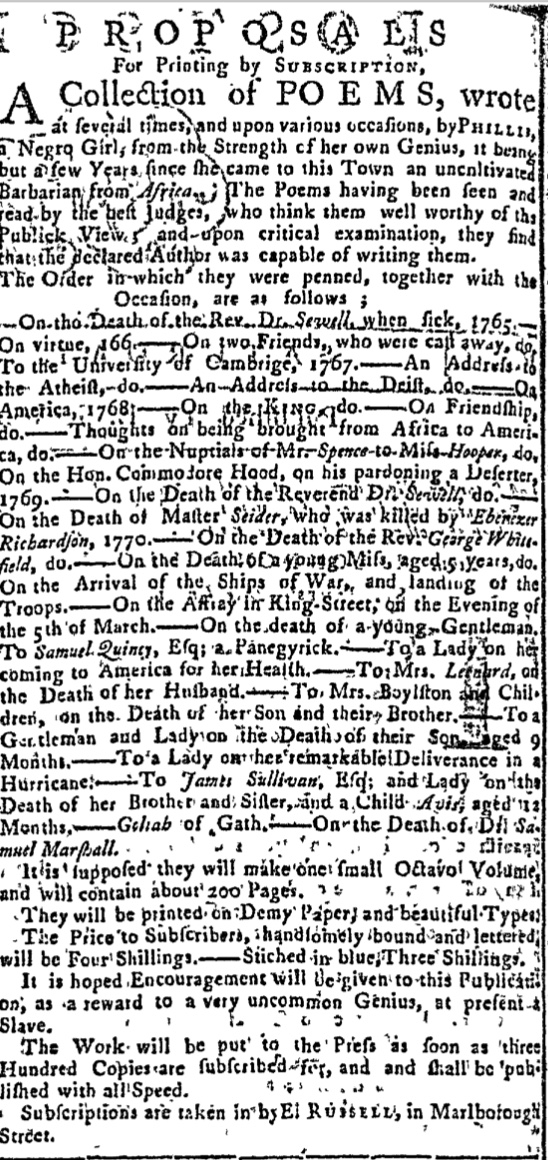

She had a breakthrough of sorts when she published her elegaic poem “On the Death of George Whitefield” in October 1770. Whitefield, the most famous preacher of the day, had preached several times in August 1770 at the Old South Church in Boston (Wheatley may have heard him then; the Wheatley family certainly knew him personally), but died unexpectedly the next month in Newburyport, Massachussetts, about 35 miles north of Boston, and was buried there. Wheatley’s poem was widely sold in New England, and then republished in London to great acclaim. The Wheatleys sought subscribers for a volume of her poetry to be published in Boston, but they do not seem to have attracted enough of them to make the venture financially viable (why they did not subsidize it themselves is unknown; they certainly could have afforded to). They turned Archibald Bell, a London publisher of religious texts, who was able to gain the patronage of Selina, the Countess of Huntington. She had been George Whitefield’s patron and was a prominent supporter of Methodist causes in England. The Countess helped subsidize the publication of Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral in 1773, which Wheatley in turn dedicated to her. Phillis Wheatley went to London (accompanied by Nathaniel Wheatley and traveling on the Wheatleys’ own ship) to supervise the printing and publication of her book, and was treated as a celebrity, meeting aristocrats and prominent public figures (including Benjamin Franklin, then resident in London officially as an advocate for the colony of Pennsylvania, but serving in general as a voice for the cause of the American colonists), and being given tours of the Tower of London and the British Museum. She returned to Boston just before the book was published, however; Susanna was ill (she died in early 1774), and Nathaniel may have prevailed upon her return to help take care of her. But, as Vincent Caretta suggests, Phillis may also have made a deal here, exchanging her willingness to return to Boston for the guarantee of her freedom. In any case, she was given her manumission in October 1773, and although she stayed a part of the Wheatley household until the death of John Wheatley in 1778, she was now a free woman.

After John Wheatley’s death, Phillis married John Peters, a free black man. She solicited subscriptions for a second volume of poetry, but with little success, and although some of the poems that would have gone into the volume were later published in newspapers, a lot of them were lost. John Peters had financial troubles and spent much time in jail for debt. He was in jail, in fact, when Phillis died of unknown causes in December 1784.

Readers immediately recognized the great skill with which Wheatley adapted contemporary English poetic forms, such as the heroic couplet and iambic pentameter blank verse, and classical models to topics such as her own enslavement and the situation of the American colonies. It is not surprising to discover that many contemporary critics had a hard time disentangling her identity as a teen-aged African-American slave from their evaluation of the quality and significance of her verse. Her publisher Archibald Bell insisted, it seems, that John Wheatley have prominent Bostonians testify that the poems were indeed by Phillis and not written by someone else, and he did so; the testimony appears at the beginning of the published Poems. Other critics enlisted her in the nascent abolitionist cause, using her obvious gifts as evidence for the equality of Africans with Europeans, and proof that slavery was immoral. As scholars in recent decades have studied and recovered her poems and letters, Phillis Wheatley’s place as one of the most important and originary voices of American literature has become secure.

(Digital facsimile of the first edition of Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, via HathiTrust)