Anne Bradstreet (1612-1672) is one of the finest poets whose writings have survived from seventeenth-century New England. She was born Anne Dudley in England in 1612 to a wealthy and influential family. Her father, Thomas Dudley, was a Puritan who became a founding member of the Massachusetts Bay Company in the late 1620s. The Company was eager to develop a Puritan-oriented colony in north America, and when they launched their their first ship, the Arbella, in 1630, Thomas Dudley went with the expectation that he would serve as the colony’s deputy governor once they arrived. Anne, who was by this point married to Simon Bradstreet, a young man who had worked with her father, joined her father and husband on the journey, arriving in what is now Salem, Massachusetts in June 1630. She spent the rest of her life in New England.

The Bradstreets were an important family in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Her father served in a number of significant administrative positions, and her husband was for many years the secretary of the colony, among many other things. Each also served as governor of the colony. Bradstreet remembered many years later that upon arrival in Massachusetts, “I came into this country, where I found a new World and new manners at which my heart rose.” The language is ambiguous, but the sense is probably that her heart did not “rise” with pleasure, but with anger and perhaps even nausea at having been displaced from a comfortable life in England to the frontier in North America. But Anne also wrote that she made her peace with her new life, accepting it as “the way of God.” The Bradstreets lived in eastern Massachusetts, in what are now Boston, Cambridge, Ipswich, and North Andover, where Simon and Anne raised eight children. Anne died in 1672, having suffered for several years from poor health, the result of smallpox and possibly tuberculosis.

In ascribing her uprooting to North America as the will of God, Bradstreet shows her loyalty to the Puritanism that infused her life, her family, her writings, and the mission of the Massachusetts Bay Company. The Puritan colonists who founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony were eager to create a world apart, what John Winthrop, the first governor of the colony called “a city upon a hill” in a sermon he gave to the assembled colonists on the Arbella as they arrived. The Massachusetts Bay Colony was a Puritan enclave run more as a theocracy than as representative democracy. The colony was officially intolerant of other religious denominations, and the colonists were eager to “civilize” the native peoples of the area (including members of the Massachusetts tribe, from which the Company and Colony took its name) by converting them to Christianity. (The Company’s seal, reproduced here, depicts, incredibly, a native American asking for such help.)

![The corporate seal of the Massachusetts Bay Company, founded in 1629. [Wikimedia Commons]](http://virginia-anthology.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Mass_Bay_Company_seal_1629.png)

What place did poetry have in such a culture? A surprisingly significant one. We tend to think of Puritans as opposed to sensual things and to aesthetic pleasures, but that is a false stereotype; the truth is closer to the opposite. Puritans worried about the sensuality of the world because they had such a healthy respect for its power that they felt the need to keep strict controls over it. They feared that indulgence in sensual things for their own sake interfered with the goal of seeing the world around us as a conduit to the divine. Human senses were a gift from God, and were thus so potent that they demanded proper control, education, and discipline. Poetry was a one way of channeling humans’ inherently sensual nature into worthwhile and uplifting pursuits, of learning how to see the world around us as so many signs of the immanent presence of God, and of shaping language so as to be able to share that insight with others. A fair number of Puritans, in both England and its colonial outpost in Massachusetts, wrote verse both for pleasure and as an expression of their faith. The famous Puritan minister Cotton Mather worried, in fact, that young ministers might spend neglect their scholarly studies by spending too much time reading and composing poetry. He observed in 1726 that the “Rickety Nation” of the Puritan people now “swarms withal” with a “Boundless and Sickly Appetite for poetry.”

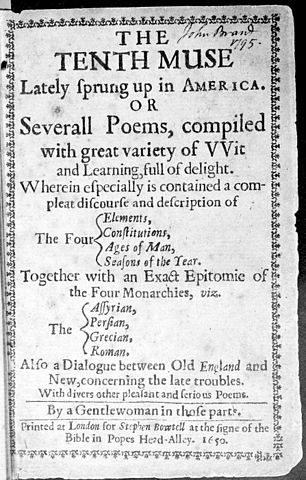

Bradstreet may have written poetry from childhood, but none of that work has survived. What we do know is that she composed poetry throughout her adult life. In most modern anthologies, the bulk of the poems reproduced concern either domestic subjects (such as “To My Dear and Loving Husband” and “Verses upon the Burning of our House” which are probably her most two famous poems for modern readers, and are included here) or her observations of the natural world in her series entitled Contemplations. And these are indeed wonderful poems, rich with observation, intimacy, and emotion. But Bradstreet also wrote on more public subjects. Her book The Tenth Muse has different series of poems on the elements, the four humours, the four seasons, and “histories” of the four great monarchies. This last is a poem that is based (at least in part) on Sir Walter Raleigh’s History of the World. These were the poems that contemporaries noticed; in his Theatrum Poetarum (1675), an enormous book that compiled the names of all of the significant poets, ancient and modern, Edward Philips identified precisely these long political poems as the ones by which “Anne Broadstreet, a New-England Poetess,” would be remembered. Her poem “A Dialogue between Old and New England” is an explicitly political work, lamenting the crisis that befell the home country in the 1640s and hoping that the godliness of its colonial offspring might help refresh it. Even on the frontier, Bradstreet kept engaged with the world beyond New England through her reading and her poetry, which addressed public and private subjects alike.

As was typical in this period, Bradstreet’s poems circulated among her family and friends in New England in manuscript form, and there is no evidence that she was interested in having them printed for wider publication. But The Tenth Muse was published in London when her brother in law John Woodbridge brought a manuscript copy of her poetry to a publisher there.

The point of the title, which was probably not Bradstreet’s idea, is that the new world has produced a new, tenth muse to add to the nine muses of the classical world, the female goddesses who, according to the Greek mythological system that early modern Europeans loved, inspired poetry. The flattering implication in 1650, a year when England was suffering from the aftermath of a terrible civil war, a war that had seen the execution of the king only the year before, was that Bradstreet was such a goddess, and that her poetry, produced in a distant land that had been spared the conflict, might help redeem the fractured culture of the home country. Bradstreet may or may not have wanted these poems published—the evidence is ambiguous—but once they were out in the world, she worked on revising her poetry and adding to her body of writing with an eye towards producing a more authoritative edition. That edition, called Several Poems Compiled with Great Variety of Wit and Learning, was published posthumously in 1678.