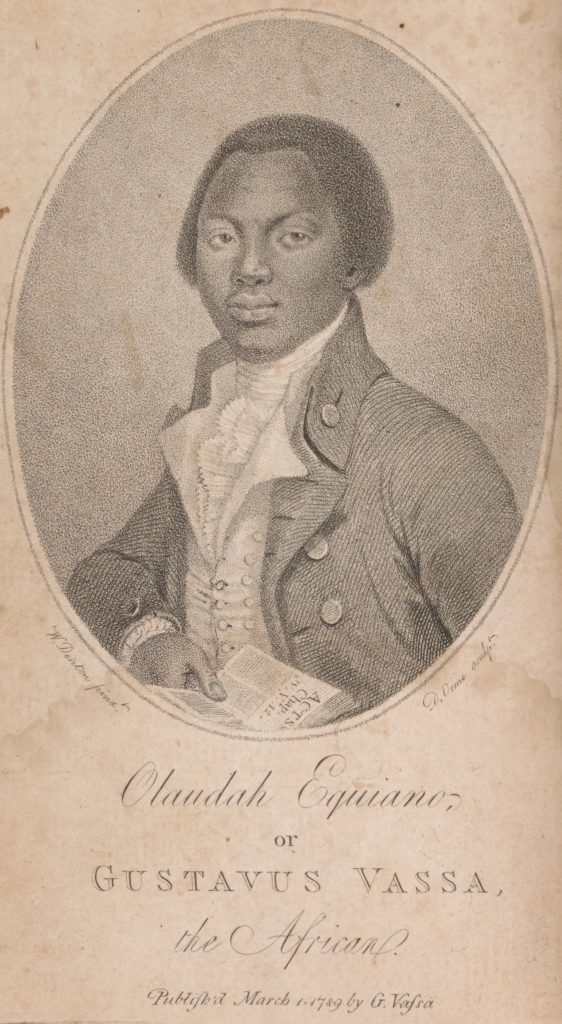

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano is the first instance in English in the genre of the slave narrative, the autobiography written by one of the millions of persons from Africa or of African descent who were enslaved in the Atlantic world between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries. Equiano’s is an extraordinary work, telling the author’s life story from his birth in west Africa, in what was then known as Essaka (in what is now the nation of Nigeria), his kidnapping, the middle passage across the Atlantic ocean in a slave ship, the brutality of the slave system in the American colonies in the Caribbean, the mainland of North America, and at sea. Equiano also tells the story of his life as a free man of color; after he was finally able to purchase his freedom in 1766, a merchant, a seaman, a musician, a barber, a civil servant, and, finally, a writer who took to the pages of London newspapers to argue on behalf of his fellow Afro-Britons before publishing this account of his life. Equiano’s book offered the first full description of the middle passage, a description harrowing in its sensory vividness:

The stench of the hold while we were on the coast was so intolerably loathsome, that it was dangerous to remain there for any time, and some of us had been permitted to stay on the deck for the fresh air; but now that the whole ship’s cargo were confined together, it became absolutely pestilential. The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. This produced copious perspirations, so that the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died, thus falling victims to the improvident avarice, as I may call it, of their purchasers. This wretched situation was again aggravated by the galling of the chains, now become insupportable; and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable. Happily perhaps for myself I was soon reduced so low here that it was thought necessary to keep me almost always on deck; and from my extreme youth I was not put in fetters. In this situation I expected every hour to share the fate of my companions, some of whom were almost daily brought upon deck at the point of death, which I began to hope would soon put an end to my miseries. Often did I think many of the inhabitants of the deep much more happy than myself. I envied them the freedom they enjoyed, and as often wished I could change my condition for theirs. Every circumstance I met with served only to render my state more painful, and heighten my apprehensions, and my opinion of the cruelty of the whites.

Equiano’s book is both a personal story and a powerful piece of testimony about the larger system of slave-trading that supported the economic system through which Britain developed a global empire. Spanning the transatlantic world, Equiano’s story powerfully captures the lived experience of slavery in the eighteenth century through the eyes of an observer with almost unbelievable resourcefulness and resilience. The book is also interesting as a literary document. Equiano is clearly familiar with the genre of the spiritual autobiography, the Puritan form of self-examination and life writing that shaped works such as Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, and he also cites English poets such as John Milton and Alexander Pope, demonstrating his mastery of the canon of great English literature. Equiano’s Interesting Narrative is one of the most absorbing, indeed interesting first-person stories of the entire century, a work that both narrates a remarkable set of experiences and shrewdly shapes it through the forms available to its author to make the case for the abolition of the slave trade.

It is important to note, however, that in the last two decades, scholars have raised doubts about the truth of some parts of Equiano’s Interesting Narrative. Vincent Carretta, probably the leading scholar in the United States on Equiano’s work and life, has discovered documents such as Royal Navy muster rolls where Equiano (identified for much of his adult life as “Gustavus Vassa,” the name given to him by Michael Pascal, his first owner) is recorded as having been born in colonial South Carolina. So too does the record of his baptism into Christianity in 1759 at St. Margaret’s Church in London. It is possible, then, that Equiano is misrepresenting his place of birth, perhaps because he believed that his story would be more compelling if he were able to describe himself as a native-born African. Other scholars have suggested that there may be other reasons to account for the discrepancy; Equiano was not responsible for creating these records, and there may be all sorts of reasons why the people who were in charge of these documents, or he, might have decided not to have identified him as having born in Africa, some of which we probably cannot reconstruct from this distance. (The British scholar Brycchan Carey provides a useful chart summing up the evidence on both sides here.) The question of where Equiano was born will probably remain unresolved until better documentary evidence or new ways of understanding the evidence that we already have become available. What no one has ever questioned is that Equiano’s Interesting Narrative is extremely accurate in its depiction of the way that the eighteenth-century slave system worked, the horrors of the middle passage, and the constant threats to their freedom and well-being experienced by free people of color, particularly in the American colonies.

The publication of the Interesting Narrative was an important event in its own right. First issued in the spring of 1789, the book was timed to coincide with a Parliamentary initiative to end Britain’s participation in the international slave trade. This was the goal of the first abolitionist movement, a movement originating largely with Quakers that was adopted and secularized by a combination of evangelical and more secular writers in the 1780s and that found its institutional centers of gravity in the largely white Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, founded in 1787, and in the Sons of Africa, a society of free persons of African descent in Great Britain in which Equiano had a leadership role. This generation of abolitionists focused on ending the slave trade rather than for the ending of slavery as an institution and the emancipation of all enslaved people in large part because they believed it to be unviable politically. Rather, they focused on ending the slave trade, arguing that if slave owners were unable to purchase new slaves kidnapped and transported from Africa, they would be forced to be more benevolent to their own slaves, and the institution would be forced to reform itself. Equiano was active in these abolitionist circles, and his book in part serves the function of a petition to Parliament to end the slave trade, with the names of the book’s subscribers identifying themselves as allies and co-petitioners in the cause. The first edition begins by including the names of 311 people who subscribed to it and thereby subsidized its printing, and later editions (nine in all in Equiano’s lifetime, a testimony to the great demand for his book) added more, eventually totalling over a thousand, as more people wanted both to own the book and to ally themselves with the abolitionist cause. Subscribers were thus taking an interest in this book in the financial sense, publicly advancing resources to support Equiano and the movement that the book was published to support. The Interesting Narrative was first printed in the United States in New York in 1791 (without Equiano’s permission, as was typical for books reprinted from Britain in the early decades of the new republic), and was widely reprinted throughout the first half of the nineteenth century.

Commons).

Equiano toured throughout the British Isles in the early 1790s, making speaking engagements to promote the abolitionist cause, and also to support sales of his book, for which he had retained copyright. This turned out to be a smart business decision; he made a fair amount of money from sales of the Interesting Narrative. Equiano married a woman from Cambridgeshire named Susannah Cullen in 1792; they had two daughters, only one of whom survived to adulthood. But neither Olaudah or Susannah was able to enjoy their married life for very long. Susanna died in 1796 and Olaudah died in 1797. The abolitionist cause to which the Interesting Narrative was a major contributor succeeded only after his death, as Britain ended its participation in the slave trade in 1807, and finally abolished slavery in its colonial holdings in 1833. Slavery in the United States continued until the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863.

About the text

Our text is derived from the Project Gutenburg edition of the Interesting Narrative, which reprints the second edition of the book.

THE

INTERESTING NARRATIVE

OF

THE LIFE

OF

OLAUDAH EQUIANO,

OR

GUSTAVUS VASSA,

THE AFRICAN.

WRITTEN BY HIMSELF.

afraid, for the Lord Jehovah is my strength and my

And in that shall ye say, Praise the Lord, call upon his

name, declare his doings among the people. Isaiah xii. 2, 4.

LONDON:

Printed for and sold by the Author, No. 10, Union-Street,

Middlesex Hospital

To the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and

the Commons of the Parliament

of Great Britain.

My Lords and Gentlemen,

May the God of heaven inspire your hearts with peculiar benevolence on that important day when the question of Abolition is to be discussed, when thousands, in consequence of your Determination, are to look for Happiness or Misery!

I am,

My Lords and Gentlemen,

Your most obedient,

And devoted humble servant,

Olaudah Equiano,

or

Gustavus Vassa.

Union-Street, Mary-le-bone,

March 24, 1789.

LIST OF SUBSCRIBERS

His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales.

His Royal Highness the Duke of York.

A

The Right Hon. the Earl of Ailesbury

Admiral Affleck

Mr. William Abington, 2 copies

Mr. John Abraham

James Adair, Esq.

Reverend Mr. Aldridge

Mr. John Almon

Mrs. Arnot

Mr. Joseph Armitage

Mr. Joseph Ashpinshaw

Mr. Samuel Atkins

Mr. John Atwood

Mr. Thomas Atwood

Mr. Ashwell

J.C. Ashworth, Esq.

B

His Grace the Duke of Bedford

Her Grace the Duchess of Buccleugh

The Right Rev. the Lord Bishop of Bangor

The Right Hon. Lord Belgrave

The Rev. Doctor Baker

Mrs. Baker

Matthew Baillie, M.D.

Mrs. Baillie

Miss Baillie

Miss J. Baillie

David Barclay, Esq.

Mr. Robert Barrett

Mr. William Barrett

Mr. John Barnes

Mr. John Basnett

Mr. Bateman

Mrs. Baynes, 2 copies

Mr. Thomas Bellamy

Mr. J. Benjafield

Mr. William Bennett

Mr. Bensley

Mr. Samuel Benson

Mrs. Benton

Reverend Mr. Bentley

Mr. Thomas Bently

Sir John Berney, Bart.

Alexander Blair, Esq.

James Bocock, Esq.

Mrs. Bond

Miss Bond

Mrs. Borckhardt

Mrs. E. Bouverie

—— Brand, Esq.

Mr. Martin Brander

F.J. Brown, Esq. M.P. 2 copies

W. Buttall, Esq.

Mr. Buxton

Mr. R.L.B.

Mr. Thomas Burton, 6 copies

Mr. W. Button

C

The Right Hon. Lord Cathcart

The Right Hon. H.S. Conway

Lady Almiria Carpenter

James Carr, Esq.

Charles Carter, Esq.

Mr. James Chalmers

Captain John Clarkson, of the Royal Navy

The Rev. Mr. Thomas Clarkson, 2 copies

Mr. R. Clay

Mr. William Clout

Mr. George Club

Mr. John Cobb

Miss Calwell

Mr. Thomas Cooper

Richard Cosway, Esq.

Mr. James Coxe

Mr. J.C.

Mr. Croucher

Mr. Cruickshanks

Ottobah Cugoano, or John Stewart

D

The Right Hon. the Earl of Dartmouth

The Right Hon. the Earl of Derby

Sir William Dolben, Bart.

The Reverend C.E. De Coetlogon

John Delamain, Esq.

Mrs. Delamain

Mr. Davis

Mr. William Denton

Mr. T. Dickie

Mr. William Dickson

Mr. Charles Duly, 2 copies

Andrew Drummond, Esq.

Mr. George Durant

E

The Right Hon. the Earl of Essex

The Right Hon. the Countess of Essex

Sir Gilbert Elliot, Bart. 2 copies

Lady Ann Erskine

G. Noel Edwards, Esq. M.P. 2 copies

Mr. Durs Egg

Mr. Ebenezer Evans

The Reverend Mr. John Eyre

Mr. William Eyre

F

Mr. George Fallowdown

Mr. John Fell

F.W. Foster, Esq.

The Reverend Mr. Foster

Mr. J. Frith

W. Fuller, Esq.

G

The Right Hon. the Earl of Gainsborough

The Right Hon. the Earl of Grosvenor

The Right Hon. Viscount Gallway

The Right Hon. Viscountess Gallway

—— Gardner, Esq.

Mrs. Garrick

Mr. John Gates

Mr. Samuel Gear

Sir Philip Gibbes, Bart. 6 copies

Miss Gibbes

Mr. Edward Gilbert

Mr. Jonathan Gillett

W.P. Gilliess, Esq.

Mrs. Gordon

Mr. Grange

Mr. William Grant

Mr. John Grant

Mr. R. Greening

S. Griffiths

John Grove, Esq.

Mrs. Guerin

Reverend Mr. Gwinep

H

The Right Hon. the Earl of Hopetoun

The Right Hon. Lord Hawke

Right Hon. Dowager Countess of Huntingdon

Thomas Hall, Esq.

Mr. Haley

Hugh Josiah Hansard, Esq.

Mr. Moses Hart

Mrs. Hawkins

Mr. Haysom

Mr. Hearne

Mr. William Hepburn

Mr. J. Hibbert

Mr. Jacob Higman

Sir Richard Hill, Bart.

Reverend Rowland Hill

Miss Hill

Captain John Hills, Royal Navy

Edmund Hill, Esq.

The Reverend Mr. Edward Hoare

William Hodges, Esq.

Reverend Mr. John Holmes, 3 copies

Mr. Martin Hopkins

Mr. Thomas Howell

Mr. R. Huntley

Mr. J. Hunt

Mr. Philip Hurlock, jun.

Mr. Hutson

J

Mr. T.W.J. Esq.

Mr. James Jackson

Mr. John Jackson

Reverend Mr. James

Mrs. Anne Jennings

Mr. Johnson

Mrs. Johnson

Mr. William Jones

Thomas Irving, Esq. 2 copies

Mr. William Justins

K

The Right Hon. Lord Kinnaird

William Kendall, Esq.

Mr. William Ketland

Mr. Edward King

Mr. Thomas Kingston

Reverend Dr. Kippis

Mr. William Kitchener

Mr. John Knight

L

The Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of London

Mr. John Laisne

Mr. Lackington, 6 copies

Mr. John Lamb

Bennet Langton, Esq.

Mr. S. Lee

Mr. Walter Lewis

Mr. J. Lewis

Mr. J. Lindsey

Mr. T. Litchfield

Edward Loveden Loveden, Esq. M.P.

Charles Lloyd, Esq.

Mr. William Lloyd

Mr. J.B. Lucas

Mr. James Luken

Henry Lyte, Esq.

Mrs. Lyon

M

His Grace the Duke of Marlborough

His Grace the Duke of Montague

The Right Hon. Lord Mulgrave

Sir Herbert Mackworth, Bart.

Sir Charles Middleton, Bart.

Lady Middleton

Mr. Thomas Macklane

Mr. George Markett

James Martin, Esq. M.P.

Master Martin, Hayes-Grove, Kent

Mr. William Massey

Mr. Joseph Massingham

John McIntosh, Esq.

Paul Le Mesurier, Esq. M.P.

Mr. James Mewburn

Mr. N. Middleton,

T. Mitchell, Esq.

Mrs. Montague, 2 copies

Miss Hannah More

Mr. George Morrison

Thomas Morris, Esq.

Miss Morris

Morris Morgann, Esq.

N

His Grace the Duke of Northumberland

Captain Nurse

O

Edward Ogle, Esq.

James Ogle, Esq.

Robert Oliver, Esq.

P

Mr. D. Parker,

Mr. W. Parker,

Mr. Richard Packer, jun.

Mr. Parsons, 6 copies

Mr. James Pearse

Mr. J. Pearson

J. Penn, Esq.

George Peters, Esq.

Mr. W. Phillips,

J. Philips, Esq.

Mrs. Pickard

Mr. Charles Pilgrim

The Hon. George Pitt, M.P.

Mr. Thomas Pooley

Patrick Power, Esq.

Mr. Michael Power

Joseph Pratt, Esq.

Q

Robert Quarme, Esq.

R

The Right Hon. Lord Rawdon

The Right Hon. Lord Rivers, 2 copies

Lieutenant General Rainsford

Reverend James Ramsay, 3 copies

Mr. S. Remnant, jun.

Mr. William Richards, 2 copies

Mr. J.C. Robarts

Mr. James Roberts

Dr. Robinson

Mr. Robinson

Mr. C. Robinson

George Rose, Esq. M.P.

Mr. W. Ross

Mr. William Rouse

Mr. Walter Row

S

His Grace the Duke of St. Albans

Her Grace the Duchess of St. Albans

The Right Hon. Earl Stanhope, 3 copies

The Right Hon. the Earl of Scarbrough

William, the Son of Ignatius Sancho

Mrs. Mary Ann Sandiford

Mr. William Sawyer

Mr. Thomas Seddon

W. Seward, Esq.

Reverend Mr. Thomas Scott

Granville Sharp, Esq. 2 copies

Captain Sidney Smith, of the Royal Navy

Colonel Simcoe

Mr. John Simco

General Smith

John Smith, Esq.

Mr. George Smith

Mr. William Smith

Reverend Mr. Southgate

Mr. William Starkey

Thomas Steel, Esq. M.P.

Mr. Staples Steare

Mr. Joseph Stewardson

Mr. Henry Stone, jun. 2 copies

John Symmons, Esq.

T

Henry Thornton, Esq. M.P.

Mr. Alexander Thomson, M.D.

Reverend John Till

Mr. Samuel Townly

Mr. Daniel Trinder

Reverend Mr. C. La Trobe

Clement Tudway, Esq.

Mrs. Twisden

U

Mr. M. Underwood

V

Mr. John Vaughan

Mrs. Vendt

W

The Right Hon. Earl of Warnick

The Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of Worcester

The Hon. William Windham, Esq. M.P.

Mr. C.B. Wadstrom

Mr. George Walne

Reverend Mr. Ward

Mr. S. Warren

Mr. J. Waugh

Josiah Wedgwood, Esq.

Reverend Mr. John Wesley

Mr. J. Wheble

Samuel Whitbread, Esq. M.P.

Reverend Thomas Wigzell

Mr. W. Wilson

Reverend Mr. Wills

Mr. Thomas Wimsett

Mr. William Winchester

John Wollaston, Esq.

Mr. Charles Wood

Mr. Joseph Woods

Mr. John Wood

J. Wright, Esq.

Y

Mr. Thomas Young

Mr. Samuel Yockney

CHAPTER I.

[A]: so sacred among them is the honour of the marriage bed, and so jealous are they of the fidelity of their wives. Of this I recollect an instance:—a woman was convicted before the judges of adultery, and delivered over, as the custom was, to her husband to be punished. Accordingly he determined to put her to death: but it being found, just before her execution, that she had an infant at her breast; and no woman being prevailed on to perform the part of a nurse, she was spared on account of the child. The men, however, do not preserve the same constancy to their wives, which they expect from them; for they indulge in a plurality, though seldom in more than two. Their mode of marriage is thus:—both parties are usually betrothed when young by their parents, (though I have known the males to betroth themselves). On this occasion a feast is prepared, and the bride and bridegroom stand up in the midst of all their friends, who are assembled for the purpose, while he declares she is thenceforth to be looked upon as his wife, and that no other person is to pay any addresses to her. This is also immediately proclaimed in the vicinity, on which the bride retires from the assembly. Some time after she is brought home to her husband, and then another feast is made, to which the relations of both parties are invited: her parents then deliver her to the bridegroom, accompanied with a number of blessings, and at the same time they tie round her waist a cotton string of the thickness of a goose-quill, which none but married women are permitted to wear: she is now considered as completely his wife; and at this time the dowry is given to the new married pair, which generally consists of portions of land, slaves, and cattle, household goods, and implements of husbandry. These are offered by the friends of both parties; besides which the parents of the bridegroom present gifts to those of the bride, whose property she is looked upon before marriage; but after it she is esteemed the sole property of her husband. The ceremony being now ended the festival begins, which is celebrated with bonefires, and loud acclamations of joy, accompanied with music and dancing.

[B]. We have many musical instruments, particularly drums of different kinds, a piece of music which resembles a guitar, and another much like a stickado. These last are chiefly used by betrothed virgins, who play on them on all grand festivals.

[C].

[D]. We beat this wood into powder, and mix it with palm oil; with which both men and women perfume themselves.

[E]. When a trader wants slaves, he applies to a chief for them, and tempts him with his wares. It is not extraordinary, if on this occasion he yields to the temptation with as little firmness, and accepts the price of his fellow creatures liberty with as little reluctance as the enlightened merchant. Accordingly he falls on his neighbours, and a desperate battle ensues. If he prevails and takes prisoners, he gratifies his avarice by selling them; but, if his party be vanquished, and he falls into the hands of the enemy, he is put to death: for, as he has been known to foment their quarrels, it is thought dangerous to let him survive, and no ransom can save him, though all other prisoners may be redeemed. We have fire-arms, bows and arrows, broad two-edged swords and javelins: we have shields also which cover a man from head to foot. All are taught the use of these weapons; even our women are warriors, and march boldly out to fight along with the men. Our whole district is a kind of militia: on a certain signal given, such as the firing of a gun at night, they all rise in arms and rush upon their enemy. It is perhaps something remarkable, that when our people march to the field a red flag or banner is borne before them. I was once a witness to a battle in our common. We had been all at work in it one day as usual, when our people were suddenly attacked. I climbed a tree at some distance, from which I beheld the fight. There were many women as well as men on both sides; among others my mother was there, and armed with a broad sword. After fighting for a considerable time with great fury, and after many had been killed our people obtained the victory, and took their enemy’s Chief prisoner. He was carried off in great triumph, and, though he offered a large ransom for his life, he was put to death. A virgin of note among our enemies had been slain in the battle, and her arm was exposed in our market-place, where our trophies were always exhibited. The spoils were divided according to the merit of the warriors. Those prisoners which were not sold or redeemed we kept as slaves: but how different was their condition from that of the slaves in the West Indies! With us they do no more work than other members of the community, even their masters; their food, clothing and lodging were nearly the same as theirs, (except that they were not permitted to eat with those who were free-born); and there was scarce any other difference between them, than a superior degree of importance which the head of a family possesses in our state, and that authority which, as such, he exercises over every part of his household. Some of these slaves have even slaves under them as their own property, and for their own use.

Though we had no places of public worship, we had priests and magicians, or wise men. I do not remember whether they had different offices, or whether they were united in the same persons, but they were held in great reverence by the people. They calculated our time, and foretold events, as their name imported, for we called them Ah-affoe-way-cah, which signifies calculators or yearly men, our year being called Ah-affoe. They wore their beards, and when they died they were succeeded by their sons. Most of their implements and things of value were interred along with them. Pipes and tobacco were also put into the grave with the corpse, which was always perfumed and ornamented, and animals were offered in sacrifice to them. None accompanied their funerals but those of the same profession or tribe. These buried them after sunset, and always returned from the grave by a different way from that which they went.

[F] sudden impulse, and ran to and fro unable to stop themselves. At last, after having passed through a number of thorns and prickly bushes unhurt, the corpse fell from them close to a house, and defaced it in the fall; and, the owner being taken up, he immediately confessed the poisoning[G].

[H], contenting myself with extracting a fact as related by Dr. Mitchel[I]. “The Spaniards, who have inhabited America, under the torrid zone, for any time, are become as dark coloured as our native Indians of Virginia; of which I myself have been a witness.” There is also another instance [J] of a Portuguese settlement at Mitomba, a river in Sierra Leona; where the inhabitants are bred from a mixture of the first Portuguese discoverers with the natives, and are now become in their complexion, and in the woolly quality of their hair, perfect negroes, retaining however a smattering of the Portuguese language.

[K]; and whose wisdom is not our wisdom, neither are our ways his ways.”

CHAP. II.

not knowing the way, I must perish in the woods. Thus was I like the hunted deer:

CHAP. III.

The author is carried to Virginia—His distress—Surprise at seeing a picture and a watch—Is bought by Captain Pascal, and sets out for England—His terror during the voyage—Arrives in England—His wonder at a fall of snow—Is sent to Guernsey, and in some time goes on board a ship of war with his master—Some account of the expedition against Louisbourg under the command of Admiral Boscawen, in 1758.

iron muzzle. Soon after I had a fan put into my hand, to fan the gentleman while he slept; and so I did indeed with great fear. While he was fast asleep I indulged myself a great deal in looking about the room, which to me appeared very fine and curious. The first object that engaged my attention was a watch which hung on the chimney, and was going. I was quite surprised at the noise it made, and was afraid it would tell the gentleman any thing I might do amiss: and when I immediately after observed a picture hanging in the room, which appeared constantly to look at me, I was still more affrighted, having never seen such things as these before. At one time I thought it was something relative to magic; and not seeing it move I thought it might be some way the whites had to keep their great men when they died, and offer them libation as we used to do to our friendly spirits. In this state of anxiety I remained till my master awoke, when I was dismissed out of the room, to my no small satisfaction and relief; for I thought that these people were all made up of wonders. In this place I was called Jacob; but on board the African snow I was called Michael. I had been some time in this miserable, forlorn, and much dejected state, without having any one to talk to, which made my life a burden, when the kind and unknown hand of the Creator (who in very deed leads the blind in a way they know not) now began to appear, to my comfort; for one day the captain of a merchant ship, called the Industrious Bee, came on some business to my master’s house. This gentleman, whose name was Michael Henry Pascal, was a lieutenant in the royal navy, but now commanded this trading ship, which was somewhere in the confines of the county many miles off. While he was at my master’s house it happened that he saw me, and liked me so well that he made a purchase of me. I think I have often heard him say he gave thirty or forty pounds sterling for me; but I do not now remember which. However, he meant me for a present to some of his friends in England: and I was sent accordingly from the house of my then master, one Mr. Campbell, to the place where the ship lay; I was conducted on horseback by an elderly black man, (a mode of travelling which appeared very odd to me). When I arrived I was carried on board a fine large ship, loaded with tobacco, &c. and just ready to sail for England. I now thought my condition much mended; I had sails to lie on, and plenty of good victuals to eat; and every body on board used me very kindly, quite contrary to what I had seen of any white people before; I therefore began to think that they were not all of the same disposition. A few days after I was on board we sailed for England. I was still at a loss to conjecture my destiny. By this time, however, I could smatter a little imperfect English; and I wanted to know as well as I could where we were going. Some of the people of the ship used to tell me they were going to carry me back to my own country, and this made me very happy. I was quite rejoiced at the sound of going back; and thought if I should get home what wonders I should have to tell. But I was reserved for another fate, and was soon undeceived when we came within sight of the English coast. While I was on board this ship, my captain and master named me Gustavus Vassa. I at that time began to understand him a little, and refused to be called so, and told him as well as I could that I would be called Jacob; but he said I should not, and still called me Gustavus; and when I refused to answer to my new name, which at first I did, it gained me many a cuff; so at length I submitted, and was obliged to bear the present name, by which I have been known ever since. The ship had a very long passage; and on that account we had very short allowance of provisions. Towards the last we had only one pound and a half of bread per week, and about the same quantity of meat, and one quart of water a-day. We spoke with only one vessel the whole time we were at sea, and but once we caught a few fishes. In our extremities the captain and people told me in jest they would kill and eat me; but I thought them in earnest, and was depressed beyond measure, expecting every moment to be my last. While I was in this situation one evening they caught, with a good deal of trouble, a large shark, and got it on board. This gladdened my poor heart exceedingly, as I thought it would serve the people to eat instead of their eating me; but very soon, to my astonishment, they cut off a small part of the tail, and tossed the rest over the side. This renewed my consternation; and I did not know what to think of these white people, though I very much feared they would kill and eat me. There was on board the ship a young lad who had never been at sea before, about four or five years older than myself: his name was Richard Baker. He was a native of America, had received an excellent education, and was of a most amiable temper. Soon after I went on board he shewed me a great deal of partiality and attention, and in return I grew extremely fond of him. We at length became inseparable; and, for the space of two years, he was of very great use to me, and was my constant companion and instructor. Although this dear youth had many slaves of his own, yet he and I have gone through many sufferings together on shipboard; and we have many nights lain in each other’s bosoms when we were in great distress. Thus such a friendship was cemented between us as we cherished till his death, which, to my very great sorrow, happened in the year 1759, when he was up the Archipelago, on board his majesty’s ship the Preston: an event which I have never ceased to regret, as I lost at once a kind interpreter, an agreeable companion, and a faithful friend; who, at the age of fifteen, discovered a mind superior to prejudice; and who was not ashamed to notice, to associate with, and to be the friend and instructor of one who was ignorant, a stranger, of a different complexion, and a slave! My master had lodged in his mother’s house in America: he respected him very much, and made him always eat with him in the cabin. He used often to tell him jocularly that he would kill me to eat. Sometimes he would say to me—the black people were not good to eat, and would ask me if we did not eat people in my country. I said, No: then he said he would kill Dick (as he always called him) first, and afterwards me. Though this hearing relieved my mind a little as to myself, I was alarmed for Dick and whenever he was calle

http://virginia-anthology.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/interestingnarrative_04_equiano_64kb.mp3

CHAP. IV.

Miss Guerins, who had treated me with much kindness when I was there before; and they sent me to school.

Guide to the Indians, written by the Bishop of Sodor and Man. On this occasion Miss Guerin did me the honour to stand as godmother, and afterwards gave me a treat. I used to attend these ladies about the town, in which service I was extremely happy; as I had thus many opportunities of seeing London, which I desired of all things. I was sometimes, however, with my master at his rendezvous-house, which was at the foot of Westminster-bridge. Here I used to enjoy myself in playing about the bridge stairs, and often in the watermen’s wherries, with other boys. On one of these occasions there was another boy with me in a wherry, and we went out into the current of the river: while we were there two more stout boys came to us in another wherry, and, abusing us for taking the boat, desired me to get into the other wherry-boat. Accordingly I went to get out of the wherry I was in; but just as I had got one of my feet into the other boat the boys shoved it off, so that I fell into the Thames; and, not being able to swim, I should unavoidably have been drowned, but for the assistance of some watermen who providentially came to my relief.

“Oh Jove! O father! if it be thy will

That we must perish, we thy will obey,

But let us perish by the light of day.”

Belle-Isle, the place of our destination; and then we had all things taken out of the ship, and she was properly repaired. This escape of Mr. Mondle, which he, as well as myself, always considered as a singular act of Providence, I believe had a great influence on his life and conduct ever afterwards.

“Wing’d with red lightning and impetuous rage;”

[M], after which[N] we went in February in 1762 to Belle-Isle, and there stayed till the summer, when we left it, and returned to Portsmouth.

CHAP. V.

[O].

To trust to hope, or dream of joy again.

* * * * * * * * * *

Where my poor countrymen in bondage wait

And as their souls with shame and anguish burn,

Pursue their toils till all his race is run.

No friend to comfort, and no hope to cheer:

[P]

“Regions of sorrow, doleful shades, where peace

And rest can rarely dwell. Hope never comes

That comes to all, but torture without end

Still urges.”

[Q]: for it is a common practice in the West Indies for men to purchase slaves though they have not plantations themselves, in order to let them out to planters and merchants at so much a piece by the day, and they give what allowance they chuse out of this produce of their daily work to their slaves for subsistence; this allowance is often very scanty. My master often gave the owners of these slaves two and a half of these pieces per day, and found the poor fellows in victuals himself, because he thought their owners did not feed them well enough according to the work they did. The slaves used to like this very well; and, as they knew my master to be a man of feeling, they were always glad to work for him in preference to any other gentleman; some of whom, after they had been paid for these poor people’s labours, would not give them their allowance out of it. Many times have I even seen these unfortunate wretches beaten for asking for their pay; and often severely flogged by their owners if they did not bring them their daily or weekly money exactly to the time; though the poor creatures were obliged to wait on the gentlemen they had worked for sometimes for more than half the day before they could get their pay; and this generally on Sundays, when they wanted the time for themselves. In particular, I knew a countryman of mine who once did not bring the weekly money directly that it was earned; and though he brought it the same day to his master, yet he was staked to the ground for this pretended negligence, and was just going to receive a hundred lashes, but for a gentleman who begged him off fifty. This poor man was very industrious; and, by his frugality, had saved so much money by working on shipboard, that he had got a white man to buy him a boat, unknown to his master. Some time after he had this little estate the governor wanted a boat to bring his sugar from different parts of the island; and, knowing this to be a negro-man’s boat, he seized upon it for himself, and would not pay the owner a farthing. The man on this went to his master, and complained to him of this act of the governor; but the only satisfaction he received was to be damned very heartily by his master, who asked him how dared any of his negroes to have a boat. If the justly-merited ruin of the governor’s fortune could be any gratification to the poor man he had thus robbed, he was not without consolation. Extortion and rapine are poor providers; and some time after this the governor died in the King’s Bench in England, as I was told, in great poverty. The last war favoured this poor negro-man, and he found some means to escape from his Christian master: he came to England; where I saw him afterwards several times. Such treatment as this often drives these miserable wretches to despair, and they run away from their masters at the hazard of their lives. Many of them, in this place, unable to get their pay when they have earned it, and fearing to be flogged, as usual, if they return home without it, run away where they can for shelter, and a reward is often offered to bring them in dead or alive. My master used sometimes, in these cases, to agree with their owners, and to settle with them himself; and thereby he saved many of them a flogging.

[R] whose slaves looked remarkably well, and never needed any fresh supplies of negroes; and there are many other estates, especially in Barbadoes, which, from such judicious treatment, need no fresh stock of negroes at any time. I have the honour of knowing a most worthy and humane gentleman, who is a native of Barbadoes, and has estates there[S]. This gentleman has written a treatise on the usage of his own slaves. He allows them two hours for refreshment at mid-day; and many other indulgencies and comforts, particularly in their lying; and, besides this, he raises more provisions on his estate than they can destroy; so that by these attentions he saves the lives of his negroes, and keeps them healthy, and as happy as the condition of slavery can admit. I myself, as shall appear in the sequel, managed an estate, where, by those attentions, the negroes were uncommonly cheerful and healthy, and did more work by half than by the common mode of treatment they usually do. For want, therefore, of such care and attention to the poor negroes, and otherwise oppressed as they are, it is no wonder that the decrease should require 20,000 new negroes annually to fill up the vacant places of the dead.

[T] And yet the climate here is in every respect the same as that from which they are taken, except in being more wholesome. Do the British colonies decrease in this manner? And yet what a prodigious difference is there between an English and West India climate?

“With shudd’ring horror pale, and eyes aghast,

They view their lamentable lot, and find

No rest!”

“—No peace is given

To us enslav’d, but custody severe;

And stripes and arbitrary punishment

Inflicted—What peace can we return?

But to our power, hostility and hate;

Untam’d reluctance, and revenge, though slow,

Yet ever plotting how the conqueror least

May reap his conquest, and may least rejoice

In doing what we most in suffering feel.”

http://virginia-anthology.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/interestingnarrative_06_equiano_64kb.mp3

CHAP. VI.

Scenes where fair Liberty in bright array

Where nor complexion, wealth, or station, can

END OF THE FIRST VOLUME.

VOLUME II

CHAP. VII.

As the form of my manumission has something peculiar in it, and expresses the absolute power and dominion one man claims over his fellow, I shall beg leave to present it before my readers at full length:

Montserrat.—To all men unto whom these presents shall come: I Robert King, of the parish of St. Anthony in the said island, merchant, send greeting: Know ye, that I the aforesaid Robert King, for and in consideration of the sum of seventy pounds current money of the said island, to me in hand paid, and to the intent that a negro man-slave, named Gustavus Vassa, shall and may become free, have manumitted, emancipated, enfranchised, and set free, and by these presents do manumit, emancipate, enfranchise, and set free, the aforesaid negro man-slave, named Gustavus Vassa, for ever, hereby giving, granting, and releasing unto him, the said Gustavus Vassa, all right, title, dominion, sovereignty, and property, which, as lord and master over the aforesaid Gustavus Vassa, I had, or now I have, or by any means whatsoever I may or can hereafter possibly have over him the aforesaid negro, for ever. In witness whereof I the abovesaid Robert King have unto these presents set my hand and seal, this tenth day of July, in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and sixty-six.

Robert King.

Signed, sealed, and delivered in the presence of Terrylegay, Montserrat.

Registered the within manumission at full length, this eleventh day of July, 1766, in liber D.

Terrylegay, Register.

FOOTNOTES:

[U] Acts, chap. xii. ver. 9.

CHAP. VIII.

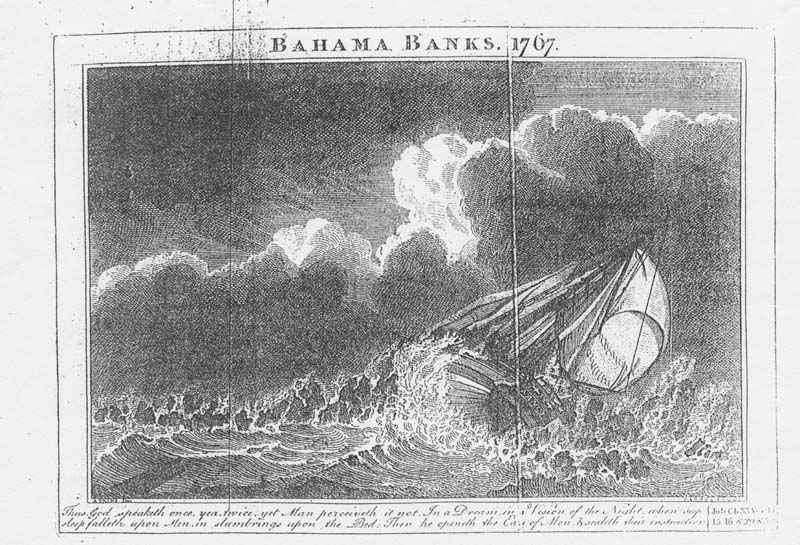

The author, to oblige Mr. King, once more embarks for Georgia in one of his vessels—A new captain is appointed—They sail, and steer a new course—Three remarkable dreams—The vessel is shipwrecked on the Bahama bank, but the crew are preserved, principally by means of the author—He sets out from the island with the captain, in a small boat, in quest of a ship—Their distress—Meet with a wrecker—Sail for Providence—Are overtaken again by a terrible storm, and are all near perishing—Arrive at New Providence—The author, after some time, sails from thence to Georgia—Meets with another storm, and is obliged to put back and refit—Arrives at Georgia—Meets new impositions—Two white men attempt to kidnap him—Officiates as a parson at a funeral ceremony—Bids adieu to Georgia, and sails for Martinico.

CHAP. IX

Montserrat, January 26, 1767.

Robert King.

are flat, and so very large, that I have known the tail even of a lamb to weigh from eleven to thirteen pounds. The fat of them is very white and rich, and is excellent in puddings, for which it is much used. Our ship being at length richly loaded with silk, and other articles, we sailed for England.

CHAP. X.

O! to grace how great a debtor

MISCELLANEOUS VERSES,

or

Well may I say my life has been

From early days I griefs have known,

And as I grew my griefs have grown:

When taken from my native land,

By an unjust and cruel band,

How did uncommon dread prevail!

My sighs no more I could conceal.

And tried my trouble to remove:

How great my guilt—how lost from God!

An orphan state I had to mourn,—

Those who beheld my downcast mien

Could not guess at my woes unseen:

They by appearance could not know

The troubles that I waded through.

With legions of such ills beside,

Unhappy, more than some on earth,

I thought the place that gave me birth—

And why thus spared, nigh to hell?—

God only knew—I could not tell!

Thrice happy songsters, ever free,

Thus all things added to my pain,

When sable clouds began to rise

My mind grew darker than the skies.

How did my breast with sorrows heave!

Yet on, dejected, still I went—

Nor land, nor sea, could comfort give,

Nothing my anxious mind relieve.

Weary with travail, yet unknown

To all but God and self alone,

Numerous months for peace I strove,

And numerous foes I had to prove.

Hard hap, and more than heavy lot!

Nothing I did could ease my pain:

Then gave I up my works and will,

Conscious of guilt, of sin and fear,

Surely, thought I, if Jesus please,

He can at once sign my release.

I, ignorant of his righteousness,

Might not his blood for me atone?

Yet surely he can make me clean!

My Saviour then I know I found,

To mourn, for then I found a rest!

My soul and Christ were now as one—

Thy light, O Jesus, in me shone!

No help in them, nor by the law:—

FOOTNOTES:

[W] Acts iv. 12.

CHAP. XI.

My soul each storm defies, while I have such a Lord.

I trust his faithfulness and power,

To save me in the trying hour.

Though rocks and quicksands deep through all my passage lie,

Yet Christ shall safely keep and guide me with his eye.

How can I sink with such a prop,

Musquito Shore, June 15, 1776.

CHAP. XII.

I had suffered so many impositions in my commercial transactions in different parts of the world, that I became heartily disgusted with the sea-faring life, and I was determined not to return to it, at least for some time. I therefore once more engaged in service shortly after my return, and continued for the most part in this situation until 1784.

To the Right Reverend Father in God,

ROBERT, Lord Bishop of London:

The MEMORIAL of Gustavus Vassa

Sheweth,

That your memorialist is a native of Africa, and has a knowledge of the manners and customs of the inhabitants of that country.

That your memorialist has resided in different parts of Europe for twenty-two years last past, and embraced the Christian faith in the year 1759.

GUSTAVUS VASSA.

No. 17, Hedge-lane.

My Lord,

I have the honour to be,

My Lord,

Humble and obedient servant,

MATT. MACNAMARA.

Grove, 11th March 1779.

March 13, 1779.

My Lord,

I am,

My Lord,

Humble and obedient servant,

THOMAS WALLACE.

My sole motive for thus dwelling on this transaction, or inserting these papers, is the opinion which gentlemen of sense and education, who are acquainted with Africa, entertain of the probability of converting the inhabitants of it to the faith of Jesus Christ, if the attempt were countenanced by the legislature.

In October 1785 I was accompanied by some of the Africans, and presented this address of thanks to the gentlemen called Friends or Quakers, in Gracechurch-Court Lombard-Street:

Gentlemen,

These gentlemen received us very kindly, with a promise to exert themselves on behalf of the oppressed Africans, and we parted.

By the principal Officers and Commissioners of

J. HINSLOW,

GEO. MARSH,

W. PALMER.

To Mr. Gustavus Vassa,

Commissary of Provisions and

Stores for the Black Poor

going to Sierra Leone.

I proceeded immediately to the execution of my duty on board the vessels destined for the voyage, where I continued till the March following.

To the Right Honourable the Lords Commissioners of

The Memorial and Petition of Gustavus Vassa a black Man,

late Commissary to the black Poor going to Africa.

humbly sheweth,

Your petitioner therefore humbly prays that your Lordships will take his case into consideration, and that you will be pleased to order payment of the above referred-to account, amounting to 32l. 4s. and also the wages intended, which is most humbly submitted.

London, May 12, 1787.

The above petition was delivered into the hands of their Lordships, who were kind enough, in the space of some few months afterwards, without hearing, to order me 50l. sterling—that is, 18l. wages for the time (upwards of four months) I acted a faithful part in their service. Certainly the sum is more than a free negro would have had in the western colonies!!!

March the 21st, 1788, I had the honour of presenting the Queen with a petition on behalf of my African brethren, which was received most graciously by her Majesty[Y]:

.

Madam,

And may the all-bountiful Creator shower on your Majesty, and the Royal Family, every blessing that this world can afford, and every fulness of joy which divine revelation has promised us in the next.

Gustavus Vassa,

The Oppressed Ethiopean.

The negro consolidated act, made by the assembly of Jamaica last year, and the new act of amendment now in agitation there, contain a proof of the existence of those charges that have been made against the planters relative to the treatment of their slaves.

The wear and tear of a continent, nearly twice as large as Europe, and rich in vegetable and mineral productions, is much easier conceived than calculated.

It is trading upon safe grounds. A commercial intercourse with Africa opens an inexhaustible source of wealth to the manufacturing interests of Great Britain, and to all which the slave trade is an objection.

If I am not misinformed, the manufacturing interest is equal, if not superior, to the landed interest, as to the value, for reasons which will soon appear. The abolition of slavery, so diabolical, will give a most rapid extension of manufactures, which is totally and diametrically opposite to what some interested people assert.

The manufacturers of this country must and will, in the nature and reason of things, have a full and constant employ by supplying the African markets.

THE END.

FOOTNOTES:

[X] See the Public Advertiser, July 14, 1787.

[Y] At the request of some of my most particular friends, I take the liberty of inserting it here.